500 million people – two-thirds of the total population of Africa – have two or more Neglected Tropical Diseases such as Lymphatic Filariasis, Onchocerciasis, Schistosomiasis, and Trachoma and need regular treatment. In addition to illness and mortality, these infections have a significant economic impact on families, communities and even countries as a whole, and result in billions of dollars of lost productivity. NTDs help to maintain poverty.

Identified as a high impact, cost-effective and deliverable intervention, tackling NTDs through mass drug distribution has recently soared on the aid and development agenda. In fact, in January 2012, the UK Department for International Development announced an aid package totalling £245m, aiming to protect an estimated 140 million people from such parasitic infections.

An emerging success story in global health: just how did NTDs move from marginal to mainstream?

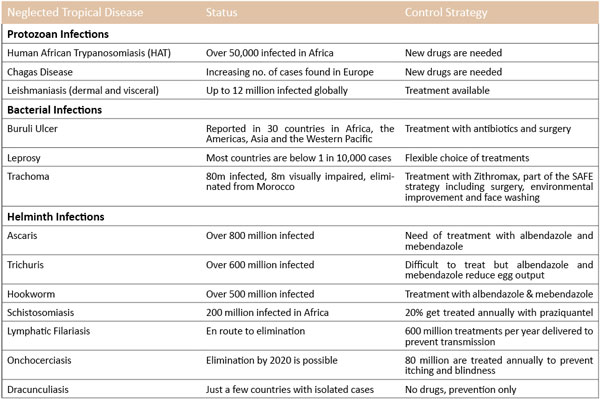

The 13 most important Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) include seven which can, and should, be controlled with the annual distribution of four drugs, all of which are donated by pharmaceutical companies or purchased for donation by foundations or governments. Another NTD – Guinea Worm – is close to eradication using health education and clean water supplies. Three others are protozoan diseases, which are killers but fortunately with limited distribution.

In 1986 the first large scale unlimited donation of a medication for annual distribution to those in need was made by the US company Merck Ltd, known in UK as MSD (Merck Sharpe Dome). This commitment for Mectizan has since protected some 100 million people in tropical Africa, in particular those who live on the banks of fast flowing rivers, against severe itching and river blindness. After 25 years of regular treatment, blindness has been virtually eliminated from Africa, although the worm has not. Thus, some 80 million people still take an annual dose of Mectizan, which prevents the worm from giving birth to the live larvae that cause the itching and blindness.

Five diseases, six worms and a bacteria, and drugs provided free of charge – where is the politics in that?

In the 1990’s it was discovered that the same drug Mectizan, if given simultaneously with Albendazole (again annually), would prevent the larvae being produced by the two worms that cause Lymphatic Filariasis (LF) – Brugia malayi and Wuchereria bancrofti. Albendazole was donated by GSK, and Merck extended their donation of Mectizan, so that all LF areas in Africa could receive the two drugs free of charge. In the Far East, where over 500 million people are at risk of LF, Albendazole (again donated by GSK) is given with DEC, which is an inexpensive drug with the same effect on larvae of LF. From 2012 to 2020, some 600 million treatments will be delivered annually and LF might well be eliminated by 2020.

Soil Transmitted Helminths (STH) are intestinal worms that can be easily treated with a single dose of (wait for it) Albendazole. Therefore everyone who is treated in the LF elimination programme also receives a deworming pill annually. However, globally up to two billion people have at least one of these worms, so many more need regular deworming.

Schistosomiasis, a parasitic water-borne worm, is widespread in Africa with an estimated 200 million infected. Again there is a treatment – Praziquantel. Between 2003 – 2007 this drug was purchased by the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) at Imperial College, using funds from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Thereafter two other funders arrived on the scene and also purchased Praziquantel for donation (the philanthropic foundation Legatum and the United States Agency for International Development, USAID). In 2009 a donation commitment was made by E. Merck Serono to provide 20 million tablets a year for 10 years. A generous donation, but not enough to treat more than 8 million children; therefore in January 2012, Merck Serono decided to increase their donation incrementally to reach 250 million tablets by 2016.

Trachoma is a disease of the eyes caused by the bacteria Chlamydia. It affects about 80 million worldwide and can be controlled by an annual dose of Zithromax. The manufacturer Pfizer now donates this drug, and in 2011 an estimated 70 million doses were provided to poor countries.

Where is the Politics?

So five diseases, six worms and a bacteria, and drugs provided free of charge – where is the politics in that? Well that’s where the politics starts: first of all, the people who are infected or at risk of these infections mostly do not know that they are infected or that their future is at risk because of these infections. Therefore we have to be proactive in bringing these drugs to the people who need them. This means that we have to persuade the relevant ministries of health and education to implement a treatment campaign.

They are unlikely to have the resources to do this, so we have to bring those resources together – funding, equipment, transport, IEC materials, training material, money for per diems etc.

If the funds are coming from donations, be it from the US government, the UK government or a foundation (Gates or ENDFUND), then a political process needs to be satisfied, often involving a competitive bidding system. This then brings into conflict the very implementing agencies that previously have all worked together and collaboratively. Even the governments themselves (and in a way it is fortunate there are just two governmental donors), DFID and USAID, have to work together to ensure their donations are not duplicating efforts, but are instead working synergistically. The World Bank also provides funding directly to governments for both health and education development. In contrast to these conflicts for funding, the pharmaceutical companies are complementing each other’s donations and working together to make the application processes for the countries much simpler. The World Health Organisation NTD department, directed by Dr. Lorenzo Savioli, now coordinates most of the donation programmes.

At present, in 2012 there are 600 million treatments for LF being delivered annually globally, with 80 million of these in Africa. There are 70 million treatments for Trachoma and 80 million against Onchocerciasis. Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminths are the poor relations with maybe only 20% of those in need having been treated in 2011. But that is all going to change over the next 4 years as increased donations come on stream – Albendazole and Mebendazole (to deworm children) and Praziquantel (to treat 100 million children annually).

Bill Gates made a huge political gesture on January 30th 2012 by bringing together the CEO’s of 13 pharmaceutical companies, several Ministers of Health from developing countries, the Director General of the World Health Organisation, a senior staffer from USAID and the World Bank. Also in attendance was the UK Minister for International Development The Hon Stephen O’Brien who, with the CEO of Merck, made two of the most amazing commitments for NTD control, including a pledge of £245m over four years (2011 – 2015) from the UK Government which marks a five-fold increase in support for NTDs.

What is needed now is peace, prosperity and good governance in all countries in Africa so that ministries of health and education can deliver the donated drugs using funds provided by governments and foundations, and technical assistance from the likes of the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative and Partnership for Child Development at Imperial College; the Centre for NTDs, Liverpool and Sightsavers which are all part of the UK Coalition for Neglected Tropical Diseases.

All these diseases have been targeted for elimination by 2020, but politics more than anything will determine whether we can achieve these goals.