China may still be classified as an emerging market, but on the Internet it has arrived. By 2015, China will add nearly 200 million users, reaching an Internet population of more than 700 million – almost double the combined number of Japan and the US.

If not by 2015, then shortly thereafter, China will likely become the largest online retail market in the world, with close to 10% of retail sales occurring online.

While China is a huge online market, it is not an easy one. Although consumers are rapidly gaining sophistication, they have their own patterns of online consumption and behaviour that are different from those of consumers in the West.

The Boston Consulting Group has regularly tracked the evolution of China’s digital consumers since 1998, and this report is the latest in our series chronicling the epic transformation of China’s consumer landscape. Companies that want to succeed in China’s consumer market must understand both these new consumers and their rapidly evolving digital lifestyles. They also need to learn how to reach, sell to, and retain these consumers as they create the world’s most important consumer market of the future.

In 2011, Chinese consumers spent 1.9 billion hours a day online – an increase of 60% from two years earlier. Far from crimping the expansion of the Internet, the government is encouraging its growth. During the current five-year plan, which runs through the end of 2015, the government has committed to spending $250 billion on broadband infrastructure. As the quality of infrastructure improves, the Chinese will be surfing the Web more often at home and at work and less often at Internet cafés. They will also be relying on their mobile phones.

In 2011, Chinese consumers spent 1.9 billion hours a day online

The Changing Face of the Internet

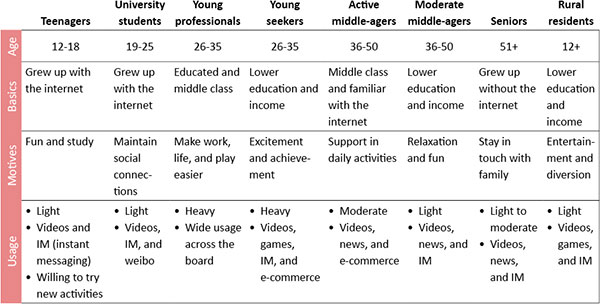

It is crucially important for companies that want to reach consumers in China to understand them on their terms and not impose mental maps drawn from other markets. In previous analysis on China’s digital generations,1 we relied on six segments, based on income and age, to provide that perspective. Those six segments are still valid but do not accommodate rapid recent growth among older generations and rural residents. Accordingly, we have added a rural and a senior segment.

The Internet in China continues to be dominated by entertainment, especially video. But there is growing usage in e-commerce, community-oriented, and information activities. The eight segments, however, do not participate in these activities equally.

Younger users tend to spend more time online but, other than young professionals, are not yet spending large sums of money online. Middle-aged users spend less time online than their younger peers, who grew up with the Internet. The willingness of middle-agers to experiment online rises with education. Although seniors and rural residents have been largely overlooked and are newer to the online world, they are rapidly making the Internet a part of their lives. Rural residents will contribute more than one-third of the Internet’s growth between 2011 and 2015 – a rate faster than between 2008 and 2011. The urban senior segment will likely grow by 22% annually between 2011 and 2015, making it the fastest-growing segment.

Over the four years that we have tracked the digital generations in China, many Internet users have moved from one segment to another or migrated to more sophisticated activities within a segment. The Internet is becoming entwined with routine activities at work and at home. While the eight segments help to illuminate the differences within China, the Internet has the power to draw the sprawling nation together, by both serving as a soapbox for a national conversation and extending companies’ commercial footprint.

The Power of Digital Dialogue

Blogging and microblogging have higher penetration rates among Internet users in China than among those in the US or Japan. Sina Weibo was launched in June 2009, after the government blocked Twitter and Fanfou, a Twitter clone. Since then, the service has grown both virally and through clever marketing. Sina Weibo has encouraged celebrities in business, show business, and the media to join, and some of them have attracted tens of millions of followers.

Weibos have become a fast-moving stream of collective consciousness. While controversy and complaints may receive the most attention, especially in the Western media, celebrity gossip is a more common form of currency. Users also post news stories, exchange photos with former classmates, and comment on recent purchases.

Rural residents will contribute more than one-third of the Internet’s growth between 2011 and 2015

This wellspring of opinions is forcing companies and the government to respond. While the role of weibos in the overall marketing landscape is still evolving, companies at least need to be able to respond swiftly and decisively when their products and services are called into question on microblogging sites and elsewhere online.

Besides crisis control, companies ought to be examining how and when they can harness the power of online conversations to burnish their brands. Vancl, an online clothing retailer, has been especially successful at this approach, which is explored later in the article. Positive commentary about products and services, in other words, can go viral just as easily as gossip and news about catastrophes.

Even the government is getting into the act. As of October 2011, government agencies across all 34 provinces had created nearly 20,000 weibo accounts. Police agencies have cracked cases with the help of clues provided through weibos. Nanjing, a city of 5 million in eastern China, has started to post air quality readings on Sina Weibo.

Environmental activists have begun to post daily or even hourly readings of air quality in China’s pollution-draped cities. The publicity generated by these readings has forced the government to revise its policies on collecting and publicizing air quality data in a nation where hundreds of thousands of premature deaths are attributable annually to air pollution.

When it comes to conversation, it is hard to put the genie back into the bottle. In late 2011, the government announced that people must start using their real names to open weibo accounts. The jury is out on whether the new rule will slow, change, or deflect the conversation.

The Fast and Furious E-Commerce Market of China

As their comfort level and sophistication have grown, users have branched out from entertaining themselves to a more diverse mix of activities including those they once avoided, notably e-commerce.

In the past two years, Chinese consumers have opened their wallets and pocketbooks online. Online buying and selling is, including group purchasing (through Chinese equivalents of Groupon) the second-fastest-growing activity, after microblogging. The country has 193 million online shoppers – more than even the US with 170 million, and five times that of the UK Between 2011 and 2015, per capita online spending will likely rise by 15% annually, more than doubling the expected overall increase in consumer spending and reflecting both the rising level of trust by consumers and the greater protections put in place by merchants. E-commerce’s share of total retailing could reach 8% by 2015.

Maturity means that future growth of the user base will slow. China’s Internet population is expected to increase by 8% annually between 2011 and 2015 – one-half the annual rate of the previous two years. However, opportunities will continue to expand, even as user growth flattens.

One of the key challenges for companies is to encourage their customers to shop online, because, our research shows, once they make the leap, they quickly become avid Internet shoppers. In focus groups, consumers who had devoted only 5% of their spending to the online channel in 2008 said they had increased the share to more than 50% by 2011. Twenty-five per cent of consumers research online before buying offline – almost as many as the 29 % who both research and buy online.

Positive commentary about products and services ... can go viral just as easily as gossip and news about catastrophes

E-commerce in China has developed its own personality. While there are analogues to Amazon and eBay in China, the nation is not on a parallel track to the US or anyplace else. There are three main types of commercial activity:

Marketplaces. Consumer-to-consumer and business-to-consumer marketplaces are frequently compared to eBay and Amazon Marketplace but have their own local flavour. Alibaba Group currently dominates consumer e-commerce in China through its Taobao consumer-to-consumer and Tmall business-to-consumer sites. More products were purchased on Taobao in 2010 than at China’s top five brick-and-mortar retailers combined, with 48,000 products sold per minute.

Taobao has worked hard to achieve this scale. It has developed extensive data-analytics capability in order to understand buying and usage patterns, created an in-house university to allow merchants to share best practices, and developed an instant-messaging system that allows buyers and sellers to share product information.

Business-to-Consumer Vertical Sites. 360buy.com is the second-largest business-to-consumer site in the country, after Tmall, and the largest that sells inventory directly to consumers. The company received a $1.5 billion cash infusion in 2011 from private investors, including Russia’s Digital Sky Technologies – one of the largest institutional investors in Facebook. It is putting the investments to work in building customer-service and logistics operations. The company is also focused on making the customer experience easy and satisfying. Besides offering cash-on-delivery payment, a simple Web interface, and a guarantee of product quality, it pledges that if a customer complains about a product, a delivery person will return within 100 minutes to take it back.

360buy.com pledges that if a customer complains about a product, a delivery person will return within 100 minutes to take it back

Business-to-Consumer Brand Sites. Vancl is the largest business-to-consumer brand site in China through several innovative online approaches to generate sales and engage with customers. The company has been an active advertiser. In 2008, the year it was founded, Vancl’s advertising budget was nearly as large as its revenues.

The company also has an active presence on Sina Weibo. The chief executive, designers, and regular employees all write posts, and the company encourages fan clubs to form and discuss clothing on Sina Weibo. As part of its weibo strategy, Vancl has offered free merchandise to celebrate Chinese Valentine’s Day. To encourage customer engagement, Vancl created its Star program. Customers post photos of themselves modeling Vancl clothing, and other users get to vote.

Capturing the Online Empire

A disconnect currently exists between how Chinese consumers spend their time and how advertisers spend their money. Advertisers have begun to increase their online spending, but the mix is still heavily skewed toward traditional media.

But the broader focus in China should be on what all companies are doing to reach and hold on to China’s digital generations. The Internet is not just another channel. A few key challenges confront companies as they sell to engage with China’s digital generations.

New business models based upon consumer insight. Companies cannot necessarily rely on what has worked in other markets, as the stumbles of many Western companies have amply demonstrated. But they can tap into the current fascination of the Chinese people with the online experience to experiment with new ways to build relationships with Chinese consumers. In particular, the popularity of weibos and online videos presents opportunities to both engage with customers and develop new revenue streams through innovative online business models.

Channel management. The channel conflicts that companies face in the West are magnified in China because of the resale of their goods on online marketplaces. Companies do not completely control the destiny of their own products. Most companies in China have barely started to explore the potential of the mobile channel. Companies need to try to develop a coherent channel strategy and build the systems to trace sales through multiple channels.

Companies need to create an integrated digital-marketing plan that emphasizes online presence and dialogue with consumers. They will have to regularly review the alignment between marketing mix and consumer trends. They must monitor and respond to online conversations about their products and services, engaging and building relationships with consumers.

A Call to Action

China has become a major Internet market with increasingly sophisticated consumers. Companies that want to win in China’s consumer market must understand both these new consumers and their rapidly evolving digital lifestyles.

To do this, they need to understand how they experience the Internet in their daily lives. Online buying and selling, including group purchasing, is the second-fastest-growing activity after microblogging.

Companies with ambitions in China should have a strong Internet presence and strategy. They need to meet their customers in the places where they spend time, and increasingly that is online.

Companies cannot win in China unless they understand and embrace China’s digital generations. They are the future of the largest consumer market in the world.